An insider’s perspective on the Hong Kong protests.

- The Eyes Journal

- Nov 26, 2019

- 8 min read

What are the Hong Kong protests? Are they really just a bunch of rioters who want to inflict damage on the society that has reared them? If not, then what are they fighting for?

The current protests in Hong Kong, also known as the anti-extradition protests, all began with the amendment of an extradition bill proposed by the Hong Kong government. The amendment of the bill (known formally as the Fugitive Orders Ordinance) allowed suspects in Hong Kong to be extradited to mainland China for trial.[1] This amendment carried heavy implications for Hong Kong political autonomy, as it violates the principle of “One Country, Two Systems”, which ensures the independence of Hong Kong’s judicial system from China’s. Hong Kong’s judiciary guarantees a trial free from executive influence, which is not the case in mainland China.

When Britain and China signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984, a document which emphasised the application of the “One Country, Two Systems” principle, the treaty was signed on the condition that the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region would “enjoy a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs”.[2] Hong Kong would have its own constitution, the Basic Law, which promises Hong Kong residents rights to freedom of speech, press, publication, assembly and more: freedoms which are not guaranteed to people under the governance of the Communist Party in Mainland China.[3]

However, in recent years, we have witnessed such freedoms being encroached upon by the Chinese government. For example, in 2014, we saw the “disappearance” of five Hong Kong booksellers in mainland China, which provoked anxieties about the true degree of freedom of publication in Hong Kong. The disqualification of six Legislative Council candidates in 2016 further called to question the nature of democracy in Hong Kong.[4] In fact, Chinese officials have blatantly denied the validity of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, claiming that the document was already “void”.[5]

The amendment of the extradition bill is not the first instance of the impingement of certain guaranteed rights. Such grievances will only keep resurfacing in greater magnitudes if the government tries to suppress the voices of the people without addressing the underlying issue. Hence the unprecedented reaction from society against the extradition bill; on 9th June, Civil Human Rights Front estimated that 1.03 million people took to the streets to participate in a peaceful protest against the amendment of the bill. Yet the voices of one-seventh of the city’s population did nothing to prevent the government from scheduling a second reading of the bill on 12th June. Chief Executive Carrie Lam simply refused to listen to the people.

On 12th June, protests outside the Legislative Council building successfully delayed the second reading of the extradition bill amendment, but at what cost? Police fired tear gas, used pepper-spray and rubber bullets in order to disperse a crowd protesting peacefully. Thus emerged the “five demands”, which called for:

1. Complete withdrawal of the extradition bill

2. Retraction of the characterisation of the June 12th protest as a “riot”

3. Release and exoneration of arrested protesters

4. Establishment of an independent commission of inquiry into police conduct and use of force during the protests

5. Universal suffrage for Legislative Council and Chief Executive elections

The extradition bill was formally withdrawn on 23rd October, after more than four months of protests, finally answering one of the “five demands”. However, by then, the movement had long since moved onto much deeper issues of grievance. Not only did the Hong Kong government renounce its responsibility to protect the people, the months of protests also saw some of the most horrifying suppression of basic human rights, most of which take the form of police brutality.

On 21st July, hundreds of white-clad men—suspected triad (a Chinese criminal organisation) members—appeared in Yuen Long station and began beating people indiscriminately with sticks and steel rods. Although police received thousands of calls for help, video footage showed two police officers turning on their heels and walking away upon observing the chaotic situation. In August, Mass Transit Railway (MTR), the major mode of transportation for Hong Kong citizens, began closing their stations in anticipation of, and even during, protests. This act denied protesters the opportunity to attend peaceful protests and, by closing off the exit route as protesters tried to leave, created panic and chaos as police deployed tear gas and rubber bullets on crowds of trapped protesters. This led to the notorious 31st August incident, in which riot police entered Prince Edward station and beat civilians indiscriminately. The station was on lockdown for thirty minutes before medical personnel were given access to injured persons. Discrepancies in the police’s initial and later reports that night led to suspicions that civilians had been killed, yet the MTR refused to release CCTV footage of that night, a copy of which was given to the police. Such incidents are indicative of many examples showing the blatant violation of freedom of demonstration and assembly in Hong Kong over the past few months.

The freedom of the press is also being targeted, such as when an Indonesian journalist was blinded by a rubber bullet fired by policemen.[6] These incidents have led to the widening of the gulf between the Hong Kong government and its people, as well as the mistrust and even antagonization of the Hong Kong police force. As incidents of police brutality increase in number, questions were raised about the overwhelming power of the police force, and cries for checks against their abuse of power become increasingly urgent. Thus, the fourth of the five demands—to establish an independent commission of inquiry into police behaviour—has become the priority of the protesters.

The existing Independent Police Complaints Council (IPCC) lacks independence from the police force as it relies on police cooperation and does not have the legal power to summon witnesses or offer protection to the victims and witnesses. Thus, it has no actual independent power to check against the police’s power abuse. This systemic flaw has attracted international concern; according to the report of the United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) in 2013.

The Committee remains concerned that investigations of police misconduct are still carried out by the police themselves through the Complaints Against Police Office (CAPO) and that IPCC has only advisory and oversight functions to monitor and review the activities of the CAPO and that the members of IPCC are appointed by the Chief Executive.[7]

During the extradition protests, many Hong Kong police officers did not present their identifying numbers on their uniforms; they often masked their faces; plainclothes officers also refused to show their police identification even when carrying out arrests. The lack of independence of the IPCC, coupled with the impossibility of identifying police officers and the increasing cases of police brutality, has led some to believe that they could no longer trust and depend on Hong Kong’s justice system.

In response to this, government officials and the Chief Executive of Hong Kong actively condemned the protesters’ violence and praised the hard work and efforts of the police The government fails to see, or chooses to ignore the core problem which has generated so much violence in society: the lack of a fully independent investigative system to act as a check against the power granted to the police. Hence, the vicious cycle continues, and the hatred between police and protesters keeps on growing.

Facing great public pressure, Carrie Lam held the first public dialogue session on 26th September, attended by 150 randomly chosen members of the public. Many of those who were given the opportunity voiced their dissatisfaction towards the Hong Kong government, expressed their loss of confidence in the police and reiterated the “five demands”. Tears were shed, and Carrie Lam expressed her wish to “receive constructive suggestions to help this government meet the public’s expectations for a more inclusive and fairer Hong Kong”.[8] Yet on 4th October, Lam bypassed all legislative procedures and invoked the anti-mask law from the Emergency Regulations Ordinance. This is a law from colonial times which empowers the government to “impose a series of draconian measures, including censorship, control and suppression of publications”.[9] Rather than listen to the demands of the people, Carrie Lam and her government imposed greater restrictions on the people of Hong Kong in an attempt to establish authoritarian control. They acted in accordance with the wishes of the Central Government, which has taken a firm and uncompromising stance against the anti-extradition protests since the beginning.

In a genuinely democratic society, the government is appointed by the people and therefore accountable to the people. It is not the case in Hong Kong, fundamentally because our Chief Executive is not elected by the people. Rather, he or she is selected from a restrictive pool of candidates supportive of the Central Government by a 1200-member Election Committee, most of whom have political or economic ties with the Central Government as well. Without a Chief Executive representative of the people, the promise of universal suffrage will never be fully realised, and the people of Hong Kong will never obtain the freedom they were promised twenty-two years ago. The actions of Carrie Lam during these months of protests have proved to the people of Hong Kong that their government is not sensitive to its people: instead, they employ well-known methods of the Chinese Communist Party to suppress the voices of Hong Kong and deny their rights. Hence their fifth demand: universal suffrage.

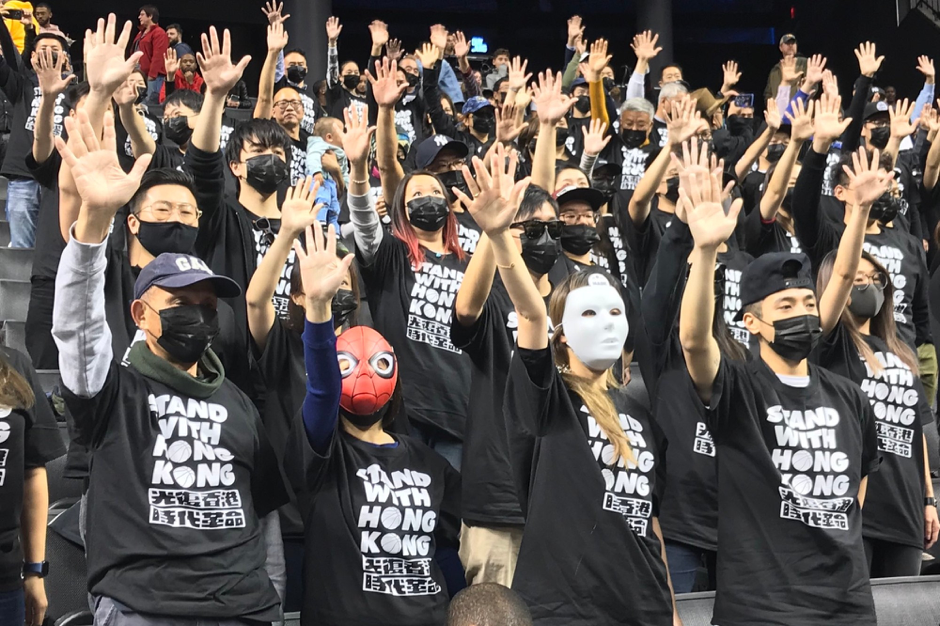

Throughout the anti-extradition protests, the Communist Party of China stands as looming figure against Hong Kong protesters; many see Hong Kong’s challenge against the Communist Party as a fight between David and Goliath. While they have not officially intervened into the protests in Hong Kong, they have been severe towards attempts to call for international help. They have asserted their authority through bullying tactics: when Houston Rockets manager Daryl Morey tweeted his support of the Hong Kong protests, China threatened to pull out of the NBA’s market. The NBA ultimately kowtowed to China by firing Morey. Large corporate companies such as Apple and Blizzard have similarly pandered to China. China is not only asserting its authority over freedom of expression in Hong Kong, it is doing so all over the world.

Yet in the face of tyranny, we have seen global solidarity with Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which assesses the conditions of political freedom and human rights in Hong Kong, has been passed by the United States Congress. The UK Foreign Secretary has spoken against police brutality, while peers and MPs have taken up the issue in the House of Lords and Commons. All around the world, groups in solidarity with Hong Kong have been established and have organised rallies to raise awareness for the situation.

Hong Kongers are not asking for independence. The portrayal of Hong Kong protesters as pro-independence rioters is a strategy employed by Chinese media to provoke hatred against a people who desire freedom and democracy. Hong Kongers are simply asking for what has been promised to them all along by the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law. Freedom is a basic human right. Protesters in Hong Kong have been very brave in their fight for freedom, but they alone are not enough in fighting such a steadfast system. The world must join and stand in solidarity with Hong Kong in their endeavour to preserve individual freedom against a global tyranny.

If you would like to know more about what you can do for Hong Kong, please like the Facebook page of “Durham Stands with HK” at: https://www.facebook.com/durhamstandswithhk/

Stand with Hong Kong. Fight for Freedom!

[1] Part 3 Clause 8 of the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill. Link here: https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr18-19/english/bills/b201903291.pdf.

[2] Paragraph 3 Part 2 of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, to be found here: https://www.cmab.gov.hk/en/issues/jd2.htm.

[3] Article 27 of the Basic Law.

[4] On the case of the ‘disappearing’ booksellers: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2058000/one-year-hong-kong-bookseller-saga-leaves-too-many-questions; regarding the ‘disqualified’ legislators, see: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/14/hong-kong-pro-democracy-legislators-disqualified-parliament.

[5] Source: South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1654603/china-says-british-complaints-over-hong-kong-visit-ban-useless.

[6] For more on the incident of the blind journalist, see SCMP: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3030864/indonesian-journalist-demands-answers-after-she-was-shot.

[7] ‘Concluding observations on the third periodic report of Hong Kong’, 2013: https://www.cmab.gov.hk/doc/en/documents/policy_responsibilities/the_rights_of_the_individuals/Advance_Version_2013_ICCPR_e.pdf.

[8] Source: The Telegraph. Link here: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/09/26/hong-kong-chief-executive-holds-public-dialogue-diffuse-tensions/.

[9] Source: The Guardian. Link here: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/05/hong-kong-emergency-law-marks-start-of-authoritarian-rule.

Author: Jeremy Chan

![2[1].jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/5abadf_f310244424a443b29215dadb17bba49b~mv2.jpg/v1/crop/x_5,y_0,w_1069,h_1080/fill/w_101,h_102,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/2%5B1%5D.jpg)

Comments