Bristol and slavery: the toppling of Colston's statue is only the beginning.

- The Eyes Journal

- Jul 2, 2020

- 5 min read

Many people heard the name ‘Edward Colston’ for the first time when his statue was pulled down, but as a Bristolian I cannot remember a time when the name ‘Colston’ was unfamiliar. However, his is not the only controversial name which remains, and this is not the first time our city’s relationship with its history has been a cause for debate. If anything, the recent protests are an arguably inevitable result of years of racism and campaigns for equality, and frustration at the lack of progress made through typical peaceful routes such as petitions.

Bristol is a diverse and multicultural city, and it is something many of us celebrate and are proud of. Every year, thousands of people enjoy St Paul's Carnival, which was created to promote unity and to be a ‘celebration of Afro Caribbean culture’. It has become ‘one of Bristol’s biggest attractions’.

The city has a history of campaigning for progressive change, although many of us arguably do not know enough about this aspect of our history or, more importantly, the causes of such campaigns. Many people are aware of Rosa Parks and her role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the mid-1950s, however there was also a Bristol Bus Boycott in 1963 led by Paul Stephenson. Evidently, we must acknowledge that this arose as a result of existing inequality and racism, but it was also influential in the passing of the Race Relations Act in 1965 which made “racial discrimination unlawful in public places”.

But we are far from innocent. We must acknowledge our history, educate ourselves, and learn from the mistakes of those who came before us. Bristol was a major slave-trade city, involved at least as early as the eleventh century, in a Britain which became ‘the most important slave-trading nation in the world’. Our city would not be the same as it is today without the money made from horrifying abuses of human rights. Edward Colston is one of those who committed such acts. While he was a merchant well-known for his generosity to Bristol charities, Colston was also a member of the Royal African Company which had a monopoly on the west African slave trade. According to David Olusoga, historian and broadcaster, ‘[Colston] helped oversee the transportation into slavery of an estimated 84,000 Africans. Of them, it is believed, around 19,000 died’. The profits he gained from this were later used to sustain schools, almshouses and churches, and in 1895 the statue was erected as a memorial to these philanthropic works.

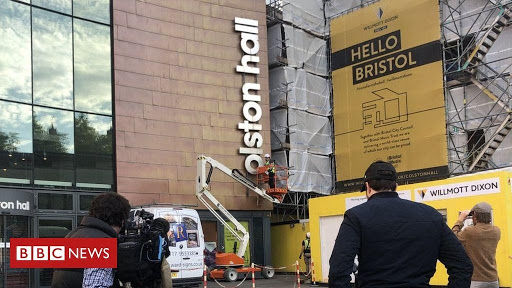

In modern Bristol, many schools, buildings and streets still bear the name of Edward Colston, so it is unsurprising that this debate about his place in our city is not a new one. In recent years, there have been campaigns to change the names of various establishments named after Colston. The Colston Hall is a well-known music venue in central Bristol, and it did in fact decide to change its name in order to represent their values as a “progressive, forward-thinking and open arts organization”, as well as the diversity of the city. Following the Black Lives Matter protests, they have decided to remove the lettering which is displayed on the outside of the building and committed to a name change by August 2020. Similarly, Colston Tower has also had its lettering removed from its exterior since the statue of Edward Colston was toppled.

With regard to the statue itself, anti-racism campaigners had campaigned for its removal for years, evidently without success. The addition of a plaque was also discussed, but the exact wording was never agreed upon and no changes were made. In 2018 Thangam Debbonaire, Member of Parliament for Bristol West, also called for the statue to be removed, saying that the city “should not be honouring people who benefitted from slavery”. Of course, there are varying opinions on the recent toppling of the statue from its pedestal. Some, such as Geoff Palmer, argue that the removal of statues is akin to ‘a slow removal of black history’. However, Olugosa wrote ‘the toppling of Edward Colston’s statue is not an attack on history. It is history’.

Accordingly, the statue has since been pulled out of the water and is to be displayed in a local museum along with placards from the protests, in order to tell the story of this historic moment. Perhaps Bristol artist Banksy’s suggestion of altering the statue to commemorate the day on which the original statue was pulled down could have been an alternative, although it would undoubtedly leave some dissatisfied. This day does mark a turning point, starting an important conversation and forcing all of us to face up to our past.

Picture posted by @banksy with the caption ‘What should we do with the empty plinth in the middle of Bristol? Here’s an idea that caters for both those who miss the Colston statue and those who don’t. We drag him out of the water, put him back on the plinth, tie cable round his neck and commission some life size bronze statues of protestors in the act of pulling him down. Everyone happy. A famous day commemorated.’ Source: Instagram

And for us Bristolians, this particular issue goes beyond Edward Colston. As one might expect of a city which was, and still is, so reliant on the profits of slavery, Colston is not the only merchant who remains in our city today after profiting from involvement in the slave trade. Many street names recall connections with the city’s involvement with Africa and the West Indies, including Jamaica Street, Tyndall’s Park, and Guinea Street. Even Bristol University has ties with slavery. Its logo comprises the crests of three families: Colston, Wills and Fry. All three are that of merchants with links to the slave trade.

In 2017, this debate over the balance between the preservation of history and the commemoration of those who profited from slavery sparked campaigns to change the name of the Wills Memorial Building, the iconic tower which is home to Bristol University’s Law School and Department of Earth Sciences. It takes its name from the Wills family who commissioned the build, and had previously donated £100,000 to the university. However, the Wills family made their money from the tobacco industry, which relied heavily on the slave trade.

The university admitted their responsibility to acknowledge their history, estimating that around 85% of the wealth used to found the university depended on the labour of enslaved people, but did not decide to change the building’s name. This is also now being reconsidered as a result of the debate started by the toppling of Colston’s statue.

Both Edward Colston and Henry Hubert Wills were among the merchants with close ties to the Society of Merchant Ventures, which helped to set up and run many of the institutions which still bear their names today. St. Monica’s Trust, which runs retirement villages and care homes, was set up by Wills and his wife in 1922, while Colston’s School was opened in 1710 as Colston’s Hospital, Edward Colston’s school for 100 poor boys. To this day, the Society of Merchant Venturers is committed to ‘helping communities across Greater Bristol to thrive’. They are educating 4,000 students across nine schools and supporting 5,000 older people.

The toppling of Edward Colston’s statue has attracted international attention and brought the question of how best to preserve history without idolising those who committed human rights abuses to the top of the agenda, with other governing bodies around the world discussing what they can do to address this issue. I am proud to live in such a diverse, vibrant, passionate, and progressive city. We are far from perfect, and we must do more, but I hope that its actions will be a catalyst for more challenging but vital conversations and long-overdue change.

Author: Eleanor Bunker

![2[1].jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/5abadf_f310244424a443b29215dadb17bba49b~mv2.jpg/v1/crop/x_5,y_0,w_1069,h_1080/fill/w_101,h_102,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/2%5B1%5D.jpg)

Comments