French counterinsurgency in the Sahel region: liberal interventionism in the colonial present

- The Eyes Journal

- Dec 19, 2019

- 5 min read

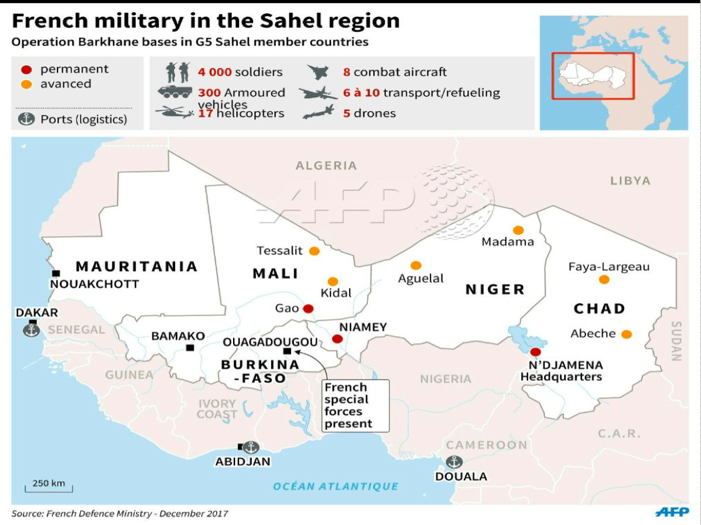

From coloniser to military occupier, France’s status in international politics is embedded in its presence in Africa. In 2012, a Tuareg rebellion in the North of Mali, later joined by the Islamists groups AQIM, Ansar Dine and MUJAO, created national unrest that culminated in a military coup and the resignation of President Touré. As a direct response to the paralysis of the Malian state, the French army launched Operation Serval in order to halt the Islamist insurgency. Operation Serval was then replaced in 2014 by Operation Barkhane, a stabilisation mission following the re-capture of all Islamist held territory, which is today the biggest French deployment in foreign operation, with around 4 000 soldiers spread across the Sahel-Saharan space in Mali, Niger and Chad.

Official reports depict a successful operation, particularly with the killing of Ali Maychou on the 6th of November, a major figure of JNIM (Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa-al Muslimin), the official branch of Al-Qaeda in Mali, and the ‘second most wanted terrorist in the Sahel’. Later the same month, France and Sahel forces also conducted an ‘unprecedented’ operation in Burkina Faso and Mali that resulted in the death of 24 terrorists. These ongoing counter-terrorist operations confirm that France is not yet ready to leave and even expressed its expectation for additional forces from European countries by 2020. This prolonged involvement in the region creates debate around the legitimacy and actual efficiency of French troops on the territory of its (ex)colony and raises questions about the risk of reproducing imperialist behaviours despite modern paradigm shifts.

In order to circumvent critiques of neo-colonialism, the strategic action plan of the operation carefully relies on three legitimising rationales: direct fight against “the ramifications of terrorist organisation […] in the Sahel-Saharan strip”[1], partnership with local and international forces, and ‘support to local population’ to allow a progressive return to normalcy in zones where the state authority was challenged. However, when deconstructed, this discourse becomes problematic as it reveals biopolitical technologies of governance that redefine knowledge about human security and sovereignty. Indeed, from a Foucauldian perspective, the control apparatus deployed in counterinsurgency operations conceptualises a form of life that requires external assistance to be completed.

Operation Barkhane’s legitimacy mainly stems from framing intervention in the context of the ‘global war on terror’, as it highlights the terrorist threat to Mali’s integrity as a nation state, and more broadly to the security of West Africa, France and Europe. Such a logic of defining the crisis as a struggle over territory rather than ideas requires to establish precise cartographies of violence and decentralises the locus of attention from Mali. The issue with this externalisation and regionalisation of the threat is that it is inherently counter-productive. First, the underlying assumption that legitimate actors are assigned to the territorial border of Mali, while terrorists belong to ungoverned and transnational space of Sahel-Sahara excludes understandings of events as the terrorist phenomenon is artificially dissociated from the national conditions which breed such movements. Then, it ignores the reality on the ground as in fact, terrorism is not contained to the arbitrary Sahel zone but also concerns countries excluded from the action perimeter such as Senegal, Algeria, Morocco, Ivory Coast, etc.

Furthermore, the practice of ‘othering’, embedded in the labelling of ‘terrorists’ and ‘Islamist threat’, depicts an outsider frame that reproduces structures of meaning located in the colonial past and re-activates relationships of power and domination. The self-appointed power to label opponents/allies and to attribute legitimacy constrains political imagination and limits the possibilities for re-founding the Malian State. Indeed, the automatic support of local leadership overlooks the agency of the state as the producer of violence and allows it to gain political capital despite its inability to address political, economic and social crises.

The efficiency and legitimacy of Operation Barkhane is also inherently impaired by its over-ambition. Indeed, in addition to leading counter-terrorist missions, troops are deployed as a stabilisation force helping partner states to acquire the capacity to ensure their security autonomously. On the ground it is reflected by the application of ‘minimum force,’ and a strategy of winning ‘hearts and minds’ through civil-military engagements, such as medical aid, support for projects related to water access, energy, health, education, etc. The articulation of the security-development nexus creates a complex assemblage of exceptionality and normalcy as it connects civil to military power, violence to order, and creates a merging of discourses of war and policing. Since decolonisation, the political discourse of liberal tutelage has been re-adapted to respect territorial integrity but ultimately, sovereignty has become internationalised, negotiable, and contingent. Despite efforts to develop a modern discourse of assistantship through ‘development,’ the governance of (in)security is entangled in the colonial present. The emphasis on the transformative potential of counterinsurgency through ‘armed social work’ reveals the essence of a liberal imperial urge to produce order.

It is also worth looking at the legal framework that allows the establishment of a system identifying Sahel as an object of governance. France was able to build on its saviour image by resorting to the legal principles of ‘intervention by invitation’ and 'collective security' in the context of a network of mobilisation sanctioned by international law, including G5 Sahel, MINUSMA, and EUTM Mali. Without oversimplifying international law as being a ‘vehicle for imperialism,’ it is nonetheless necessary to mention that the elasticity of what constitutes a ‘threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression,’ and the devices of ‘implied authorisation’ and ‘intervention by invitation’ reflect an increasing permissiveness regarding the extraterritorial use of force. International law progressively institutionalises new security mechanisms that have both a responsive and stabilising dimension. Hence, the rationale of collective security is at once biopolitical, liberal, and police-oriented, and ultimately reprograms contemporary sovereignty and global governance through a variety of securitising techniques with regulatory rather than judicial functions.

Ultimately, not only French military presence in the Sahel region is not achieving its aims, but it is also symptomatic of a system of liberal interventionism relying on the governance of (in)security and the problematisation of the population as a whole. Indeed, the political rationale of counterinsurgency enacts existential threats that legitimise exceptionalist policies and normalised pervasive securitisation of the social life. The parallel evocation of security and development in counterinsurgency strategies create a paradox between the power to eliminate life in the framework of the ‘war on terror’, and the power to protect life through ‘hearts and minds’ tactics. Hence, it is paramount to think critically about the future of interventionism and the compatibility between biopower and sovereign power, and the role it plays on the (re)production of subjectivities in the colonial present.

Author: Laura Le Ray

[1] “Dossier de presse Barkhane,” French Ministry of defence, last modified October 28, 2019: 7. Available at:

https://www.defense.gouv.fr/operations/barkhane/dossier-de-presentation/operation-barkhane

![2[1].jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/5abadf_f310244424a443b29215dadb17bba49b~mv2.jpg/v1/crop/x_5,y_0,w_1069,h_1080/fill/w_101,h_102,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/2%5B1%5D.jpg)

Comments