Nord Stream II: Russia’s latest ‘Energy Weapon’?

- The Eyes Journal

- Oct 12, 2018

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 2, 2019

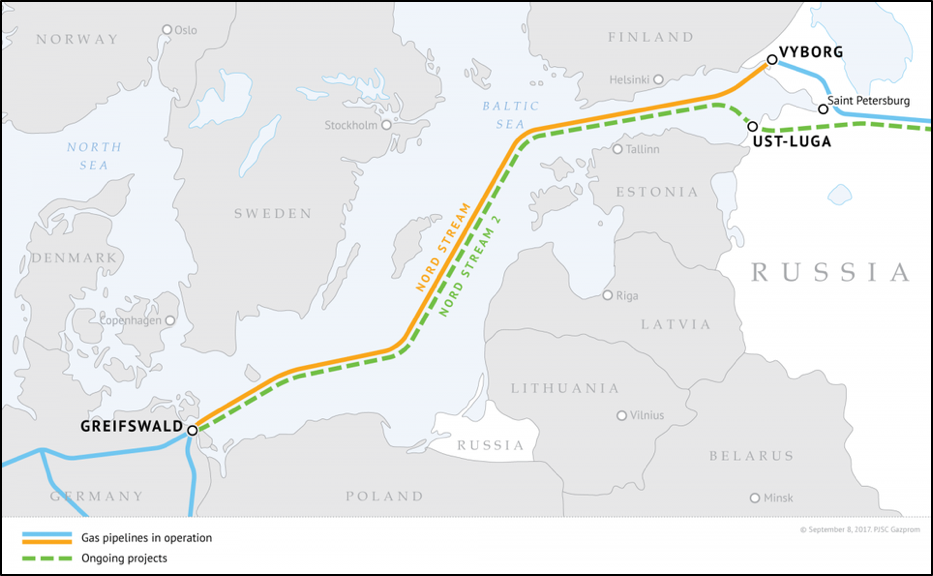

Proposed Nord Stream II route. Gazprom.

Nord Stream II, the new export gas pipeline that will travel across the Baltic Sea from Russia to Europe, has become the latest example of Russia’s foreign policy strategies abroad. The pipeline is supposedly a commercial project, aiming to increase the amount of gas exported directly from Russia to Germany. However, the extent to which the new project is genuinely a commercial venture or rather a geopolitical move against Ukraine (of which Russia currently exports gas to Europe through Ukrainian pipelines), is a question worth exploring.

Europe needs more gas. With a decline in domestic gas production having sparked a greater demand for imported gas throughout the continent, what makes this project anything but a commercial affair? The answer lies in Russia’s ever-existent expansionist policy. Subsisting not far beneath the surface of this seemingly harmless project, lies an extensive geopolitical scheme in which Russia’s sphere of influence continues to increase. Europe’s ever-growing dependence on Russia’s highly reliable gas supply and Ukraine’s economic and strategic reliance on the Russian gas transit puts the country in an increasingly favourable place in terms of strategic international relations. With Nord Stream II increasing Germany’s reliance on cheap Russian gas, there is concern that it will result in the country taking a more tolerant stance towards Russia on the international stage.

The increase in Russian military presence in eastern Ukraine is an attempt by Putin to punish their ‘western-oriented’ government and unite “Russian-speaking peoples” into a Eurasian bloc, and Nord Stream II is simply an extension of this. Ukraine, whose role as a transit country plays a crucial part in their ability to withstand further Russian aggression, stands to lose billions in transit fees currently collected from the vast network of pipelines used by Russia to transport gas to Europe. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is only getting worse, and following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine operates in constant fear for its eastern provinces in case of an escalation in Russian military operations.

Ukrainian fears of Russian aggression became a reality last month when three Ukrainian ships were seized in the Kerch Straight, the access point to the Sea of Azov. Whilst Moscow threw accusations of illegal entry into Russian waters at the 24 sailors, Kiev remained firm that the ships had the right to access the straights in order to reach its Ukrainian ports. The influence of Nord Stream II on the German response to the standoff is disappointing but predictable. With numerous members of the European Union, and even the United States considering prohibiting Russian ships travelling from the Sea of Azov from entering their ports, Merkel was merely able to muster up a call on Russia to release the ships, without talk of imposing any sanctions. The German Chancellor insists that Germany’s continued involvement in the project is done so in protection of Ukrainian interests. In advocating for the continuation of gas transit routes through Ukraine, Merkel believes that the project gives them political influence over Russian energy policy toward Ukraine. Despite these promises, it is apparent even now that Russia’s ‘energy weapon’ has discouraged Germany in reprimanding countless wrongdoings and is rendering gas transport through Ukraine as superfluous.

Ukraine gas pipeline network. National Gas Union of Ukraine.

A brief review of the recent Human Rights abuses in Russian-occupied Crimea begs the question as to why, whilst many Western countries have imposed sanctions on Russia, support for Russian-led international projects like Nord Stream II are able to develop with minor levels of outside influence. A recent UN human rights report discusses Russia’s violation of the Geneva Conventions and numerous ‘international humanitarian and human rights laws’ following Moscow’s imposition of Russian law and citizenship on the residents of Crimea. It is obvious that Putin’s regime seeks to increase its influence in Ukraine, with its presence becoming increasingly violent. In the September 25 report regarding the temporary occupation of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol (Ukraine), it is stated that ‘grave human rights violations, such as arbitrary arrests and detentions, enforced disappearances, ill-treatment and torture, and at least one extra-judicial execution were documented’.

Whilst the European Commission proposed that making Nord Stream II subject to EU law and regulations could reduce the risk of negative consequences materialising, the potential of this becoming a reality remains low, as numerous member states whose companies support the project have been successful thus far in blocking the ruling.

Concern should rise over Moscow’s numerous attempts to minimise investigations into the political motives behind Nord Stream II. Moscow’s pressure on the investigations is so strong as to force political writer and journalist, Yulia Latynina, to flee the country after conducting her own independent research into the pipeline, in which she stated it was “of course a geopolitical project”. In addition, earlier this year Russia’s largest bank, Sberbank, published a report that criticised Gazprom’s numerous projects as making no commercial sense as the project will apparently ‘never pay itself back’, as stated by Mikhail Krutikhin, an analyst at RusEnergy. The report’s lead author, Alexander Fak, was fired shortly after the report was published and his work deemed as ‘unprofessional’. Krutikhin has previously stated that he believes there exist only two possible reasons for the Kremlin to promote this project: to punish Ukraine in rendering their gas transit links as unnecessary and thus crippling their economy, and for Gazprom’s contractors to take an easy payday.

Behind the charade, there exists little room for doubt that the project is more of a geopolitical move than a commercial one, if it can be described as a commercial project at all. But, what does Russia seek to gain from the new pipeline? If the political undercurrent beneath Nord Stream II is as sinister as it appears, then it is time that Putin is warned that the project does not come without its conditions, and that the countries involved do not shy away from imposing them when the time inevitably arrives.

Author: Charlotte Gardner

![2[1].jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/5abadf_f310244424a443b29215dadb17bba49b~mv2.jpg/v1/crop/x_5,y_0,w_1069,h_1080/fill/w_101,h_102,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/2%5B1%5D.jpg)

Comments