Turkey’s system of ‘torpil’: Erdoğan and his system of ‘favourites’

- The Eyes Journal

- Feb 12, 2020

- 5 min read

How does a highly contested and frequently challenged leader hold on to power in the modern world? For Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Turkish president, the answer is through strategies of camouflage and co-optation, or in other words ‘gaming the system’.

Since its establishment of power in 2002, the AK Party has faced several crises, including an attempted military coup in July 2016 and the questionable June 2018 elections, which resulted in the implementation of the executive presidential system that we see in Turkey today. The vote greatly reduced the legislative powers held by parliament, instead transferring them into the hands of president Erdoğan and leaving the parliament ineffective and useless. Some argue that the new system makes the government more efficient, by giving the president even more power. However, by taking such vast amounts of decision-making authority away from parliament, can we expect anything less than for the president to abuse his newly increased and almost irrefutable power?

Erdoğan’s system of ‘torpil’ is nothing new. In fact, it is not a new concept in Turkey at all. It is the widespread informal practice that revolves around finding private solutions to public problems in bureaucracy- for example ‘torpil’ relations can be used to find jobs for oneself or one’s relatives, to skip queues in hospitals and even to acquire free healthcare. One of the definitions of ‘torpil’ published by the Turkish Language Institute is ‘favouring someone over others’. This can be applied to various forms of corruption in the Turkish government and beyond, as seen with various examples of probable clientelism in the country, the asymmetric relationship between groups of political actors in exchange of goods and services for political support. This mutually beneficial relationship can be said to exist between the Turkish president and the owners of mass media in Turkey. The idea that Erdoğan has developed a system of ‘favourites’ is only encouraged by Turkey’s nepotism fears (the practice among those with power or influence of favouring relatives or friends, for example by giving them jobs) after the president made his son-in-law finance minister in 2018. Whilst one is generally unaware of their own ‘torpil’ networks and interactions and they are mostly viewed as ‘harmless favouritism’, this deep-rooted system in Turkish society must be more widely recognised if change is to be implemented. If these forms of informal practices are left to exist in the shadows, key figures in government using them to advance their own corruption will continue to go unquestioned and unpunished. In Turkey, ‘torpil’ is widely used in the context of employment, it also implies influence and protection of parties involved. For example, one is able to see how Erdoğan continuously ‘protects’ his allies or hires those closest to him, whether they be friends, or family. A study conducted in 2015 and published in the Turkish newspaper, Cumhuriyet, found that eighty-five relatives of government ministers were given senior positions across several ministries, without having to pass competitive state examinations. Although, there was little to no public outcry or distain with the news as the majority of Turkish people are not only accustomed to the practice of ‘torpil’, but they believe they may also have benefited from its use or hope to in the future and thus do not see it as something to eradicate from Turkish society.

(For more information on ‘torpil’- please visit: http://www.in-formality.com/wiki/index.php?title=Torpil_(Turkey))

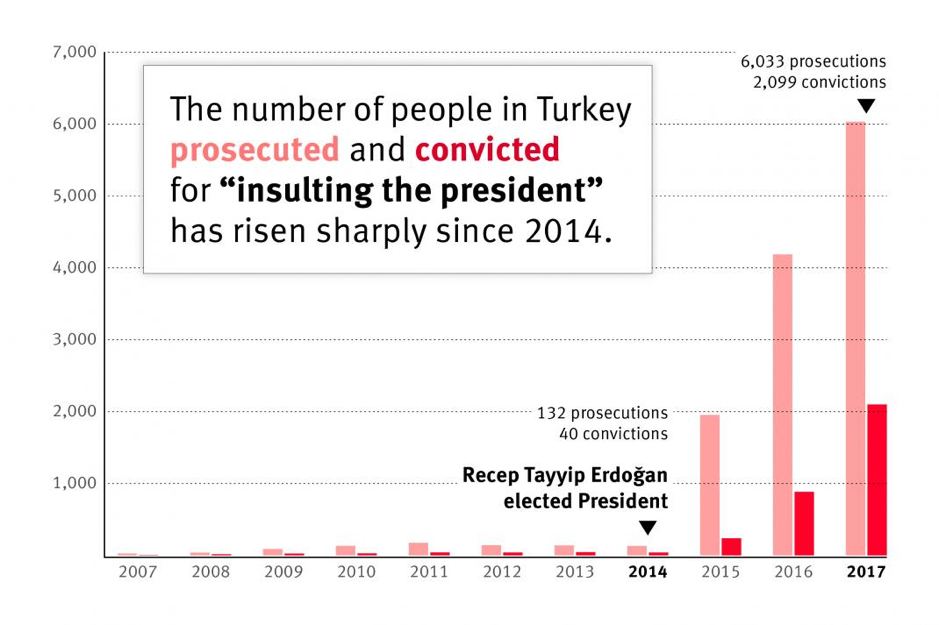

The practice of ‘torpil’ is dangerously recognised as a harmless practice in Turkey, however what is not often noted is that there exists a direct causal relationship between the system of ‘torpil’ and the enabling of corrupt activities. President Erdoğan’s relationship with the country’s powerful media owners has been a constant tool in enabling his corruption. In Turkey, 40% of all media are owned by eight different groups (Media Ownership Monitor Turkey, 2019). Four of these major media owners have investments in at least three out of four media types. This results in a concentration of influence over radio, TV, newspapers and online outlets in Turkey. It is of great interest to examine the relationship between Erdoğan’s popularity in the polls at election time, and his coverage across national television. Figures obtained by the Turkish TV and radio watchdog state that during the 2018 Turkish elections, president Erdoğan received 181 hours of coverage by state broadcaster TRT, whereas his biggest rival, Muharrem Ince, received only 15 hours. Despite Ince having addressed mass crowds of a claimed 4 million at a rally in Istanbul shortly prior to the election, it would be impossible to infer this from any coverage on the major TV channels in Turkey. As a result of the overwhelming majority of media being owned and controlled by allies of the president, a loyalist press is established. It must be noted that those who take a critical standpoint to the government in Turkey, or the president, have been seen to face prosecution. Human Rights Watch (2016) produced a report that found the Turkish government guilty of using the criminal justice system to prosecute critical journalists with made-up charges. Critical journalists to the President have been jailed for acts of terrorism, crimes against the state or for offensive activities. They also found evidence of the Turkish government buying critical private media companies and closing them down or restricting their access to the airwaves and given large fines.

(For more information on the Human Rights Watch report- Silencing Turkey’s Media please visit: https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/12/15/silencing-turkeys-media/governments-deepening-assault-critical-journalism)

(For more information on media ownership in Turkey- please visit: http://seenpm.org/owns-media-turkey-media-ownership-monitoring-project/ )

Erdoğans use of ‘torpil’ is undeniably obvious through the relationship between media outlets who are loyal to his regime, and those who receive major tenders from the government. The owners of media in Turkey are mostly businessmen who have additional interests and projects elsewhere. If one examines the likes of the Albayrak group, the Turkuvaz/Zirve/Kalyon group, İhlas group and Doğuş in Turkey, all major media ownership groups, and their support for president Erdoğan, it is undeniable that there exists a mutually beneficial relationship. All of the above mentioned groups have won major public tenders from the Turkish government in recent years, ranging from the construction of the third airport in Turkey, to urban redevelopment projects. Holding companies who are sympathetic to the government are frequently favoured to receive billions of dollars in government contracts, whereas those who are critical of the government often find themselves targets of tax investigations or are forced to pay large and baseless fines. The Doğan group, for example, publishes critical content of the Turkish government and whilst they also have major investments outside of the realm of media, they have not received any major tenders from the government for several years.

The president also raised fears of nepotism, with the previously mentioned appointment of his son in law as minister of Finance. Erdoğan’s new role as executive president has placed fear not only into the markets, who are concerned about his interest in the Central Bank, but also into those who fear Turkey’s turning its back on democracy, allowing for corruption to reign amongst the upper echelons of government without intervention.

What is clear in Turkey, is that president Erdoğan is not averse to using his own system of ‘torpil’ to advance and maintain his power status. The AKP government has not been quiet in its efforts to suppress the media’s role as a counter-check on its power, and president Erdoğan has been slowly building an impenetrable wall of loyalist supporters with his newfound ability to appoint ministers and vice-presidents and intervene in the legal system.

Author: Charlotte Gardner

![2[1].jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/5abadf_f310244424a443b29215dadb17bba49b~mv2.jpg/v1/crop/x_5,y_0,w_1069,h_1080/fill/w_101,h_102,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/2%5B1%5D.jpg)

Comments